January 09, 2025

6 min read

A 53-year-old woman presented to an outside provider with 1 day of bilateral floaters and “smoke/foggy” vision.

She had a medical history of Graves’ disease on daily levothyroxine and breast cancer treated with chemotherapy, radiation and mastectomy. She had an ocular history of thyroid eye disease and refractive error.

Source: Noha A. Sherif, MD, and Lianna Valdes, MD

A thorough review of systems was negative, including no history of trauma, tattoo swelling, travel outside of the United States, insect bites and use of blood thinners.

Ocular vitals and anterior segment exam were within normal limits. Posterior segment exam was remarkable for bilateral posterior vitreous detachments and bilateral hemorrhages in the macula and periphery. At this time, the patient was diagnosed with hypertensive retinopathy and started on 40 mg of lisinopril daily. Three months later, the hemorrhages resolved, but the “foggy” vision persisted, and the patient now had 1+ vitritis bilaterally. She was subsequently referred to the New England Eye Center for further evaluation.

Examination

Upon presentation to the New England Eye Center, visual acuity was 20/30 in both eyes. IOP was 12 mm Hg in the right eye and 15 mm Hg in the left eye. The pupils were round, reactive and without a relative afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular movements were full without pain. Color vision was full. Anterior segment exam was unremarkable. Posterior segment exam was notable for bilateral posterior vitreous detachments and 1+ vitritis. There was a small intraretinal hemorrhage along the inferotemporal arcade in the right eye and no heme present in the left eye. Few creamy yellow-white ovoid lesions were found nasal to the optic disc in the left eye (Figure 1).

What is your diagnosis?

See answer below.

Vitritis, pale chorioretinal lesions

White dot syndromes should be at the top of the differential in the setting of bilateral posterior uveitis and pale chorioretinal lesions. Lesions in birdshot retinochoroidopathy (BRC) are often found nasal to the optic disc (Minos and colleagues). Infectious causes should also be considered in the differential, including tuberculosis, syphilis, histoplasmosis and endogenous endophthalmitis. Lymphoma can present with similar clinical features to BRC, including the appearance of white dots on the retina. Lymphoma is especially important to include on the differential, particularly in elderly patients with a history of cancer.

Workup and management

Workup of bilateral posterior uveitis with chorioretinal lesions should begin with a thorough history including demographics, travel, systemic disease, medical history/compliance/response, social history and trauma. Following a detailed ocular exam, relevant laboratory testing should be ordered, including uveitis panels, CBC, CMP, ESR/CRP, ANA, RF, anti-CCP, ANCA, ACE/lysozyme, RPR/FTA-ABS and QuantiFERON Gold. Relevant ocular imaging should be obtained, including color fundus photos, autofluorescence and fluorescein angiography (FA) to start. Additional imaging and laboratory tests should be ordered based on clinical suspicion. In this case, in which the leading diagnosis was BRC, additional testing and imaging included human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A29, OCT of the macula, indocyanine green (ICG) angiography and electroretinography (ERG).

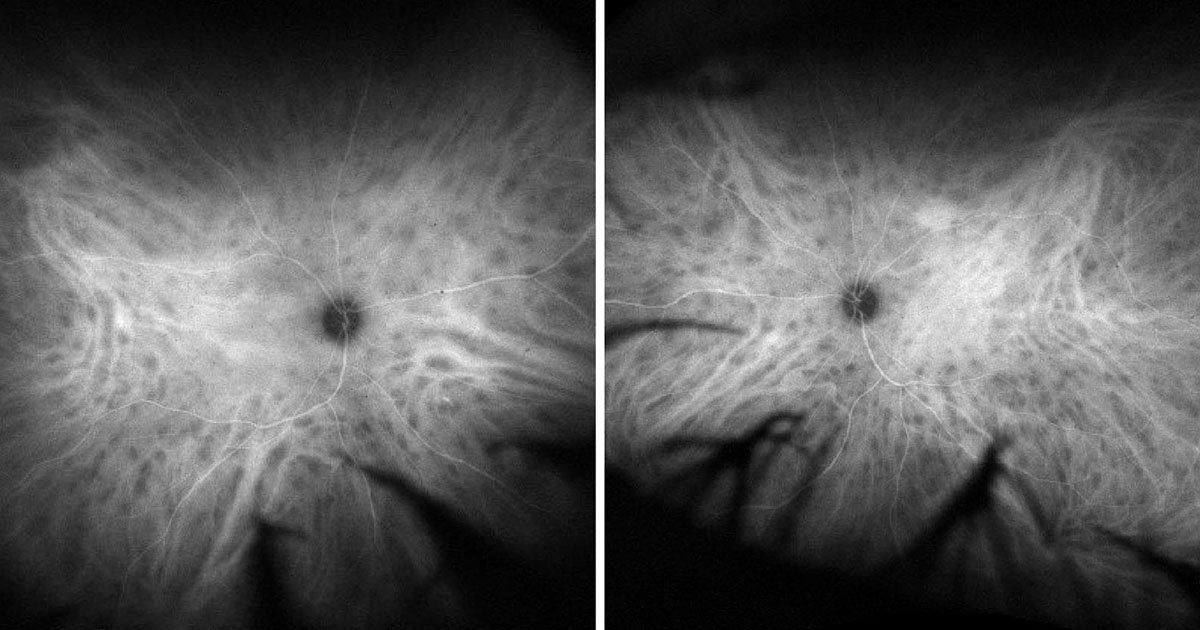

In this case, the uveitis panels were within normal limits. However, the patient did test positive for HLA-A29. Color fundus photos of the left eye demonstrated inferonasal and nasal cream-colored or yellow-white chorioretinal lesions radiating from the optic disc (Figure 1). Late-phase FA of the right and left eyes demonstrated phlebitis (Figure 2). Late-phase ICG angiography revealed scattered hypocyanescent spots bilaterally (Figure 3). Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated nasal and superior chorioretinal lesions not seen on FA (Figure 4). The patient was started on daily 50 mg prednisone over 6 weeks with follow-up during the steroid taper to assess resolution of lesions with repeat testing and potential need to escalate treatment.

Discussion

Birdshot retinochoroidopathy is a rare, chronic bilateral posterior uveitis primarily affecting the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid. It is strongly associated with HLA-A29, making it one of the most genetically linked forms of uveitis, as it is found in approximately 80% to 98% of patients with BRC (Kiss and colleagues). The disease predominantly affects individuals of Caucasian descent, typically in the 40- to 60-year-old age range, with a slight female predominance (Monnet and colleagues). The etiology of BRC is not fully understood but is believed to involve autoimmune mechanisms mediated by T cells (Th17), triggered by environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals (LeHoang and colleagues).

The clinical presentation of this condition is often with nonspecific visual symptoms most commonly including blurry vision, floaters, nyctalopia, dyschromatopsia and/or photophobia (Rothova and colleagues). Given the nonspecific visual symptoms, diagnosis of this condition is based on clinical exam and imaging findings. Funduscopic exam typically reveals characteristic cream-colored hypopigmented oval choroidal lesions scattered inferior to the optic disc (Minos and colleagues). Additional findings may include optic disc swelling, vascular leakage, cystoid macular edema (CME) and diffuse retinal vascular attenuation (Minos and colleagues).

The required criteria for diagnosing BRC include bilateral pathology, three or more peripapillary birdshot lesions, 1+ anterior vitreous cells or less, and 2+ vitreous haze or less (Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group). Criteria that support the diagnosis of BRC include HLA-A29 positive serology, retinal vasculitis and CME. Criteria that exclude the diagnosis of BRC include keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, and other infectious, neoplastic or inflammatory pathology causing underlying disease (Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group). ICG angiography, the gold standard imaging modality to diagnose BRC, will reveal more fundus lesions than visible on FA or on clinical exam. These lesions are well-delineated hypocyanescent spots seen during the mid and late phases (Fardeau and colleagues). Electroretinography will demonstrate dysfunction of photoreceptors characteristically with decreased B-wave amplitude, increased latency time and prolonged 30 Hz flicker implicit time (Sobrin and colleagues). If present, OCT can help detect CME, subretinal fluid or atrophy of the retinal layers.

Of note, early identification and diagnosis of BRC are challenging as classic lesions are often absent/subtle on exam or fundus photography, especially early in disease. Additionally, ICG angiography is not readily available. Researchers have found that certain patterns on FA have a high positive predictive value for BRC, specifically, a contiguous, perineural retinal vascular leakage pattern on FA (Li and colleagues). If this leakage pattern is identified in patients for whom BRC is suspected, it can prompt providers to refer patients for ICG angiography and HLA-A29 testing and lead to early diagnosis and treatment (Li and colleagues).

The management of BRC includes therapies that help control inflammation. Systemic corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for acute inflammation (Menezo and colleagues). Either oral or localized therapies, such as intravitreal steroid injections or implants, can be used to manage acute flares or as a bridge to immunosuppressive agents for chronic disease. Often, long-term immunosuppression with immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) is required. Commonly used IMT agents include antimetabolites (eg, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine), calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine A, tacrolimus) and biologics (eg, adalimumab, infliximab). Patients undergoing these treatments should receive extensive counseling on systemic side effects as well as ocular side effects, such as the development of elevated IOP or cataracts with steroid use (Menezo and colleagues).

With early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, the prognosis of BRC has improved significantly. However, untreated or poorly managed cases may result in irreversible vision loss due to chronic inflammation and complications such as CME or retinal atrophy. For example, without treatment, it has been reported that approximately 16% to 22% of patients develop visual acuity of 20/200 or less over 10 years as compared with patients treated with IMT who maintain stable or improved vision in 78.6% to 89.3% of cases (Kiss and colleagues). Additionally, it is important to remember to treat BRC with systemic therapy. There is a limited role for topical and/or localized treatment because BRC is an aggressive disease, and local therapy alone will not adequately control inflammation (Menezo and colleagues).

Clinical case continued

Three weeks after starting therapy, the patient returned for follow-up and was found to have pigmented and chronic-appearing cells in the vitreous with no active vitreous inflammation. Repeat ICG angiography continued to demonstrate hypocyanescent spots in both eyes, although significantly reduced since presentation (Figures 5a and 5b). There was a low threshold to start IMT as her symptoms and disease were unresolved and given the potentially high morbidity of the disease. It was recommended to the patient that she initiate IMT, but she declined, preferring to repeat testing after a complete steroid course. The reason for this preference was because the patient previously experienced systemic side effects from immunosuppressive chemotherapy treatment of her breast cancer, which served as a reminder in this case of the importance of patient agency and shared decision-making. The patient will be followed closely during the steroid course to carefully monitor disease progression and potential need for treatment escalation.

- References:

- Fardeau C, et al. Ophthalmology. 1999;doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90403-7.

- Kiss S, et al. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006;doi:10.1097/00004397-200604620-00006.

- Kiss S, et al. Ophthalmology. 2005;doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.036.

- LeHoang P, et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;doi:10.1076/0927-3948(200003)811-SFT049.

- Li A, et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2024;doi:10.1080/09273948.2022.2150228.

- Menezo V, et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;doi:10.2147/OPTH.S54832.

- Minos E, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;doi:10.1186/s13023-016-0429-8.

- Monnet D, et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.067.

- Rothova A, et al. Ophthalmology. 2004;doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.031.

- Sobrin L, et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.053.

- Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.059.

- For more information:

- Edited by William W. Binotti, MD, and Julia Ernst, MD, PhD, of New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine. They can be reached at william.binotti@tuftsmedicine.org and julia.ernst@tuftsmedicine.org.

Leave a Reply