Click here to view the original post by Healio Ophthalmology.

In addition to our own original articles, the Retina Consultant team expertly curates relevant news and research from leading publications.to provide our readers with a comprehensive view of the retina & ophthalmology landscape, Full credit belongs to the original authors and publication.

By clicking the link above, you will be leaving our site to view an article from its original source.

Sharpen your perspective. Get our weekly analysis of the news shaping the retina industry.

December 06, 2024

6 min read

A 70-year-old man presented for an urgent visit to the retina clinic for sudden painless vision loss of his right eye.

The patient had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, coronary artery disease status post quadruple bypass and type 2 diabetes. Notably, he had been followed for mild to moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy in both eyes without other significant findings for several years and had not seen an ophthalmologist for nearly 8 months at the time of acute presentation. No therapy had been initiated during these prior encounters, including prophylactic panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal injections, even after extensive conversation as the patient was known to be apprehensive about proceeding with any treatment while not having any visual symptoms.

Source: James Kwan, MD, and Jeffrey Chang, MD

Examination

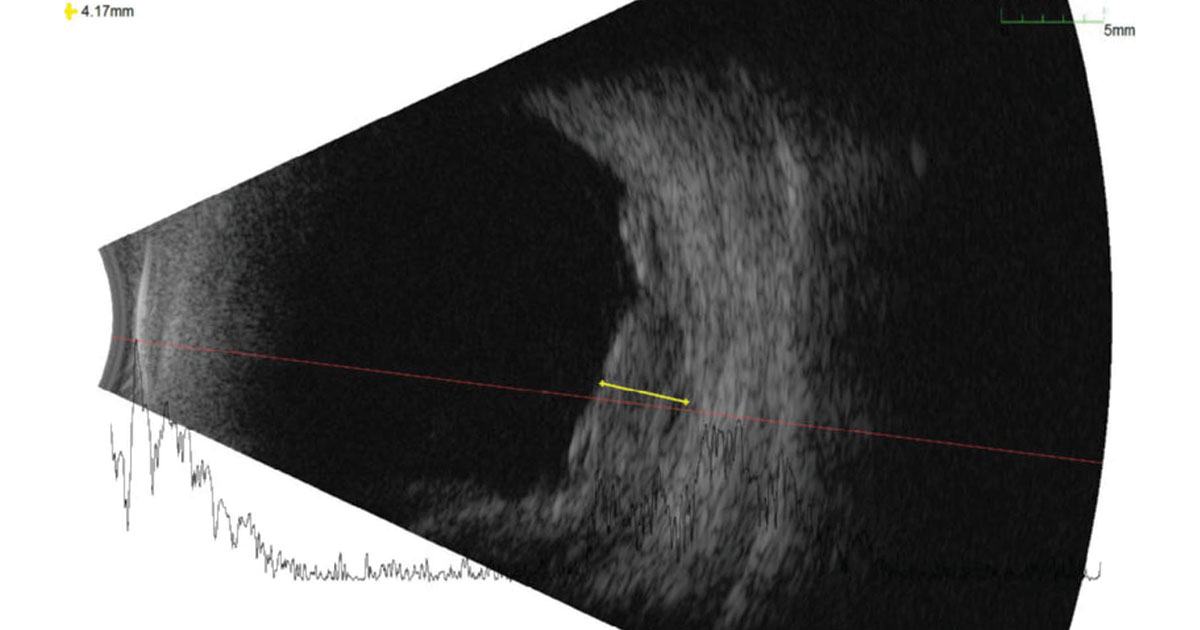

Upon urgent evaluation, the patient reported that he had been experiencing a shade in his right visual field for 4 days. Visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left. IOPs and pupils were normal. Visual fields by confrontation and extraocular movements were full. Anterior segment examination was unrevealing, demonstrating bilateral cataracts and no iris neovascularization. The posterior segments of both eyes demonstrated findings consistent with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; however, the periphery of the right eye had a large elevation of the retina inferotemporally, inferiorly and inferonasally, with associated shifting subretinal hemorrhage (Figure 1). No clear retinal break or tear was identified, although the peripheral examination was challenging. The left eye was unremarkable. B-scan of the right eye showed an approximately 4 mm irregular elevation of moderate inner reflectivity (Figure 2). Fluorescein angiography demonstrated one area of inferotemporal leakage and a central pinpoint area of exudation.

What is your diagnosis?

See answer below.

Peripheral retinal elevation

The differential for a presumed acute onset peripheral retinal elevation associated with a subretinal hemorrhage was broad. Possible etiologies to consider were age-related macular degeneration, spontaneous myopic choroidal hemorrhage, retinal macroaneurysm and trauma. However, despite the patient’s age, there had not been previous evidence of AMD; additionally, his manifest refraction was +1.75 +0.75 × 170 in the right eye, his blood pressure was moderately well controlled, and he denied any history of trauma. Rarely, diabetic retinopathy has been reported to cause a subretinal hemorrhage and may also be considered; however, none of these pathologies seemed likely at the time.

Furthermore, the differential for a pigmented peripheral lesion was important to consider in this case. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), reactive hyperplasia of the RPE, choroidal nevi, melanoma, choroidal hemangioma, peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy, nodular posterior scleritis and retinal dystrophies are entities that may present as focal or confluent peripheral hyperpigmented lesions. Given that several of these entities should prompt systemic workup and/or aggressive treatment, it is crucial to consider and appropriately test for them.

Diagnosis and initial management

After extensive discussion, it was decided to observe this patient with close follow-up. Upon the next encounter, a small increase in central subretinal fluid was noted with a concomitant decrease in central visual acuity in the right eye to 20/100. Otherwise, there was a largely stable hemorrhagic inferior detachment noted on examination. However, given that an underlying mass could not be ruled out as the etiology for an acute bleed, a referral to ocular oncology was made.

Three days later, the patient presented to this referral without further significant changes to the right eye. Repeat testing was performed, including B-scan ultrasonography, and it was determined that his presentation was most consistent with peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR). Administration of intravitreal bevacizumab was recommended at this time given central involvement of the subretinal fluid and decreased vision to address any contribution of diabetic macular edema that may have been present.

Next steps

Unfortunately, the patient experienced a breakthrough vitreous hemorrhage with further decline in his vision 2 days after his first intravitreal injection. He sought a second opinion given the acute change, and it was felt that PEHCR was still the most likely diagnosis and to return to ocular oncology. Two weeks later, his vision was hand motion only. Repeat B-scan ultrasonography did not demonstrate extension of subretinal hemorrhage to the macula. Given the poor view to the posterior segment and significantly decreased vision, there was a discussion regarding proceeding with a pars plana vitrectomy with intravitreal bevacizumab vs. continued observation; the patient ultimately elected to proceed with surgical management, which he underwent 3 weeks later without complication. The postoperative course was uneventful, and 4 months later, the patient’s vision in the right eye had improved to 20/40 with only chronic peripheral heme noted on examination.

Discussion

PEHCR is a degenerative condition of the peripheral retina and choroid. The incidence of PEHCR is not known but is thought to be low. White women in their seventh or eighth decade of life are most likely to be affected (Shields and colleagues). Despite the paucity of published reports, hypertension, increased age, use of antiplatelets or anticoagulation, and possibly concurrent diagnosis or features of age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy have been identified as risk factors for PEHCR. Similarly, the pathophysiology is not well understood, although it is thought that there may be overlap with AMD, given the shared demographic and reported concurrence in presentation (Elwood and colleagues).

Typically, PEHCR is a bilateral process with reports ranging from 30% to 40%, and commonly reported features include peripheral subretinal and sub-RPE hemorrhage, RPE hyperplasia or atrophy, and subretinal fluid (Shields and colleagues). Patients are usually not symptomatic, and features of PEHCR may be incidentally identified during a dilated eye examination. However, when vitreous hemorrhage or subretinal fluid or hemorrhages involves the macula, profound vision loss may result.

Because of its appearance as a mass-like pigmented lesion, PEHCR is frequently mistaken to be a choroidal nevus or melanoma and is considered a “pseudomelanoma,” which also includes choroidal nevus, congenital hypertrophy of the RPE, hemorrhagic RPE detachment, choroidal hemangioma, AMD and RPE hyperplasia, among several others (Shields and colleagues). It is also important to note that while PEHCR more commonly presents with a hemorrhagic component, an exudative subtype exists and may be a masquerader of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (Safir and colleagues).

Imaging is useful in characterizing PEHCR and may help differentiate between other possibilities on the differential. OCT showed a variable association with pigment epithelial detachments, and B-scan ultrasonography typically demonstrated lesions with moderate to high internal reflectivity, which is notably distinct to that of a choroidal melanoma (Shields, Elwood).

The management of PEHCR varies by the degree of symptoms. In most cases, careful observation and referral to an ocular oncologist are reasonable, when suspicious. The literature highlights that the majority of PEHCR lesions self-resolve (Shields and colleagues). When sight-threatening subretinal fluid or hemorrhage is present, administration of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections may be considered; however, no studies have demonstrated visually significant response to this therapy (Elwood, Vandefonteyne). Pars plana vitrectomy is another therapeutic option, specifically for non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage. Long-term follow-up with these patients is indicated to ensure no progression, sequential involvement or other presenting features that may suggest an alternative diagnosis.

Where is the patient now?

Six months after undergoing pars plana vitrectomy of the right eye (2 months after most recent postoperative visit), the patient urgently reported sudden onset dense floaters and decreased vision in the previously unaffected left eye. He had a vitreous hemorrhage and confluent inferior sub-inner limiting membrane hemorrhage. The examination of the periphery was partially obscured but grossly flat. Given the similarity in presentation from the right eye, the patient was diagnosed with a sequential breakthrough vitreous hemorrhage secondary to underlying PEHCR in the contralateral eye. The patient chose to observe, and 3 days later, increased vitreous hemorrhage with corresponding decreased vision to counting fingers at 3 feet was noted. The patient received intravitreal bevacizumab and elected to proceed with pars plana vitrectomy of the left eye. At the most recent follow-up for his postoperative day 1 visit, the patient’s vision had improved to 20/60. Thus, this case highlights the importance of long-term follow-up in these patients.

- References:

- Benson MD, et al. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2019;doi:10.1177/2474126419873547.

- Elwood KF, et al. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;doi:10.3390/medicina59091507.

- Gowda A, et al. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024;doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2023.10.004.

- Li J, et al. Ophthalmology. 2019;doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.06.011.

- Safir M, et al. PLoS One. 2022;doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275163.

- Shields CL, et al. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000041.

- Shields CL, et al. Ophthalmology. 2009;doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.015.

- Shields JA, et al. Retina. 2005;doi:10.1097/00006982-200509000-00013.

- Vandefonteyne S, et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313307.

- Ylmaz Çebi A, et al. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2023;doi:10.3205/oc000211.

- For more information:

- Edited by William W. Binotti, MD, and Julia Ernst, MD, PhD, of New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine. They can be reached at william.binotti@tuftsmedicine.org and julia.ernst@tuftsmedicine.org.

Leave a Reply